How to prepare for rising heat

This coverage is made possible through a partnership with WABE and Grist, a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future.

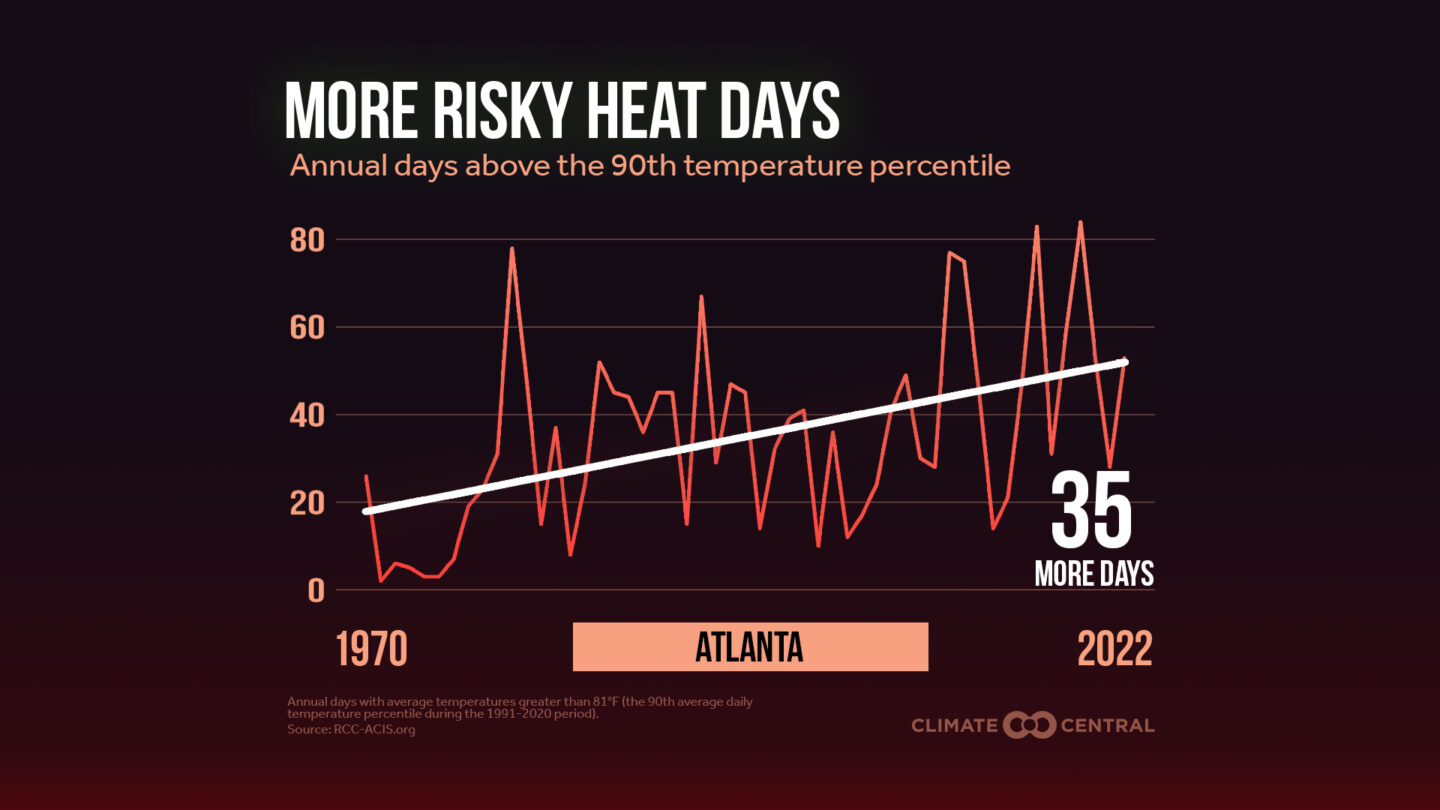

As climate change makes heat waves longer and more intense — and summers hotter overall — experts said there are steps people and communities can take to stay safe.

The basics of heat safety are written into the weather reports whenever there is a heat warning: hydrate, stay in air conditioning if possible, and check on vulnerable neighbors and relatives. Take breaks in the shade if you’re working outside.

But extreme heat is here to stay, so it’s important to prepare for it.

“Gradually getting our bodies used to the heat earlier can help prepare us for later in the summer, so long as we continue to maintain that,” said Samantha Scarneo-Miller of West Virginia University, who studies exertional heat illness — the dangerous health impacts of working or exercising in extreme heat.

Starting small with maybe a 15-minute walk as the morning starts to heat up, and then working your way up to exercise longer can get the body more used to heat, according to Scarneo-Miller. And that makes illness due to the heat less likely.

But individuals acclimatizing to heat won’t counteract the extreme temperatures climate change is causing. Scarneo-Miller said organizations that require people to be active outside, like workplaces and sports leagues, also need to take action to keep people safe. That means tangible preparation, like having tubs ready for ice water immersion to combat heat stroke, as well as intangible steps.

“[Make] sure that you’re promoting an environment where your employees or your athletes, the people who you are supervising, feel comfortable and supported to tell you if they’re not feeling well,” Scarneo-Miller said.

Ultimately, bigger changes will likely be required, like moving sports practices and work shifts away from the hottest parts of the day, according to Scarneo-Miller

There are also ways to cool the immediate environment. For individuals, wearing a white shirt instead of a black one can make a huge difference. The same is true for houses and cities: dark paving materials and roofs soak up heat, making the areas around them hotter and buildings harder to cool down.

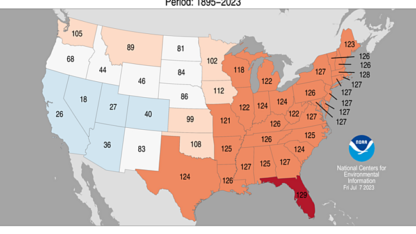

Writ large, this phenomenon produces the urban heat island effect, in which cities are measurably hotter because of their concentrations of pavement and relative lack of trees. In Atlanta, just over half the population experiences eight degrees of extra heat due to this phenomenon, according to a recent analysis by Climate Central.

Scientists have found that changes like using lighter roofs and pavements and planting more trees can reduce the urban heat island effect.

“If I’m in a public school, or in a public building, that roof, instead of absorbing most of the sunlight, instead bounces it back into space, and it leaves the atmosphere, literally cooling the planet,” said Greg Katz, founder of the Smart Surfaces Coalition, which advocates for such solutions. “That means the temperature in the building is lower.”

Solutions like that have been around for decades and are even mentioned in Atlanta’s 2015 climate action plan. But so far, experts say, they haven’t been adopted widely enough. In an effort to change that, the coalition recently selected Atlanta and a handful of other cities to do detailed mapping of the possible impacts of these changes.

“We’re developing a customized, online, very powerful analytic engine for Atlanta which uses satellite data to map exactly all of the surface attributes,” Katz said. “You run a hundred scenarios, and now all of a sudden, you can kind of see what your future is going to look like. And you can shape your future.”

Georgia Tech professor and Urban Climate Nexus CEO Jairo Garcia, who helped develop Atlanta’s 2015 climate plan, said he hopes this latest effort can make a dent. For that to happen, he said city leaders would need to write surface-cooling solutions into building codes — and enforce them.

“If you don’t force people to change their ways,” he said, “They don’t change.”